Napoleonic Wars

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of conflicts declared against Napoleon's French Empire and changing sets of European allies by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionized European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to the application of modern mass conscription. French power rose quickly, conquering most of Europe, but collapsed rapidly after France's disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812. Napoleon's empire ultimately suffered complete military defeat resulting in the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France. The wars resulted in the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and sowed the seeds of nascent nationalism in Germany and Italy that would lead to the two nations' consolidation later in the century. Meanwhile the Spanish Empire began to unravel as French occupation of Spain weakened Spain's hold over its colonies, providing an opening for nationalist revolutions in Spanish America. As a direct result of the Napoleonic wars the British Empire became the foremost world power for the next century,[1] thus beginning Pax Britannica.

No consensus exists as to when the French Revolutionary Wars ended and the Napoleonic Wars began. One possible date is 9 November 1799, when Bonaparte seized power in France with the coup of 18 Brumaire. 18 May 1803 is probably the most commonly used date, as this was when a renewed declaration of war between Britain and France (resulting from the collapse of the Treaty of Amiens), ended the only period of general peace in Europe between 1792 and 1814. The latest proposed date is 2 December 1804, when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor.

The Napoleonic Wars ended following Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo on 18 June 1815 and the Second Treaty of Paris.

Background 1789–1802

The French Revolution of 1789 had a significant impact throughout Europe, which only increased with the arrest of King Louis XVI of France in 1792 and his execution in January 1793 for "crimes of tyranny" against the French people. The first attempt to crush the French Republic came in 1793 when Austria, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of Naples, Prussia, Spain and the Kingdom of Great Britain formed the First Coalition. French measures, including general conscription (levée en masse), military reform, and total war, contributed to the defeat of the First Coalition, despite the civil war occurring in France. The war ended when General Bonaparte forced the Austrians to accept his terms in the Treaty of Campo Formio. Only Great Britain remained diplomatically opposed to the French Republic.

The Second Coalition was formed in 1798 by Austria, Great Britain, the Kingdom of Naples, the Ottoman Empire, Papal States, Portugal, Russia, Sweden and other states. During the War of the Second Coalition, the French Republic suffered from corruption and internal division under the Directory. France also lacked funds, and no longer had the services of Lazare Carnot, the war minister who had guided it to successive victories following extensive reforms during the early 1790s. Napoleon Bonaparte, the main architect of victory in the last years of the First Coalition, had gone to campaign in Egypt. Missing two of its most important military figures from the previous conflict, the Republic suffered successive defeats against revitalized enemies whom British financial support brought back into the war.

Bonaparte returned from Egypt to France on 23 August 1799, and seized control of the French government on 9 November 1799 in the coup of 18 Brumaire, replacing the Directory with the Consulate. He reorganized the French military and created a reserve army positioned to support campaigns either on the Rhine or in Italy. On all fronts, French advances caught the Austrians off guard and knocked Russia out of the war. In Italy, Bonaparte won a victory against the Austrians at Marengo (1800). But the decisive win came on the Rhine at Hohenlinden in 1800. The defeated Austrians left the conflict after the Treaty of Lunéville (9 February 1801), forcing Britain to sign the "peace of Amiens" with France. Thus the Second Coalition ended in another French triumph. However, the United Kingdom remained an important influence on the continental powers in encouraging their resistance to France. London had brought the Second Coalition together through subsidies, and Bonaparte realized that without either defeating the British or signing a treaty with them he could not achieve complete peace.

Start date and nomenclature

No consensus exists as to when the French Revolutionary Wars ended and the Napoleonic Wars began. Possible dates include 9 November 1799, when Bonaparte seized power in France;[2] 18 May 1803, when Britain and France ended the only period of peace in Europe between 1792 and 1814, and 2 December 1804, when Bonaparte crowned himself Emperor.

Sources in the UK occasionally refer to the nearly continuous period of warfare from 1792 to 1815 as the Great French War, or as the final phase of the Anglo-French Second Hundred Years' War, spanning the period 1689 to 1815.[3]

War between Britain and France, 1803–1814

Unlike its many coalition partners, Britain remained at war throughout the period of the Napoleonic Wars. Protected by naval supremacy (in the words of Admiral Jervis to the House of Lords "I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea"), the United Kingdom maintained low-intensity land warfare on a global scale for over a decade. Despite such assurance by Admiral Jervis, evidence can still be seen of the beacon warning towers built in the event of such an invasion, for example, at Eston Nab, near Middlesbrough. The British Army gave long-term support to the Spanish rebellion in the Peninsular War of 1808–1814. Protected by topography, assisted by massive Spanish guerrilla activity, and sometimes falling back to massive earthworks (The Lines of Torres Vedras), Anglo-Portuguese forces succeeded in harassing French troops for several years. By 1815, the British Army would play the central role in the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

The Treaty of Amiens (25 March 1802) resulted in peace between the UK and France, but satisfied neither side. Both parties dishonored parts of it: the French intervened in the Swiss civil strife (Stecklikrieg) and occupied several coastal cities in Italy, while the UK occupied Malta. Bonaparte tried to exploit the brief peace at sea to restore the colonial rule in the rebellious Antilles. The expedition, though initially successful, would soon turn to a disaster, with the French commander and Bonaparte’s brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc, dying of yellow fever and almost his entire force destroyed by the disease combined with the fierce attacks by the rebels.

Hostilities between Britain and France renewed on 18 May 1803. The Coalition war-aims changed over the course of the conflict: a general desire to restore the French monarchy became closely linked to the struggle to stop Bonaparte.

Bonaparte declared France an Empire on 18 May 1804 and crowned himself Emperor at Notre-Dame on 2 December.

Having lost most of its colonial empire in the preceding decades, French efforts were focused mainly in Europe. Haiti had won its independence, the Louisiana Territory had been sold to the United States of America, and British naval superiority threatened any potential for France to establish colonies outside Europe. Beyond minor naval actions against British imperial interests, the Napoleonic Wars were much less global in scope than preceding conflicts such as Seven Years' War which historians would term a "world war".

In 1806, Napoleon issued the series of Berlin Decrees, which brought into effect the Continental System. This policy aimed to eliminate the threat from Britain by closing French-controlled territory to its trade. Britain maintained a standing army of just 220,000 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, whereas France's strength peaked at over 2,500,000, as well as several hundred thousand national guardsmen that Napoleon could draft into the military if necessary; however, British subsidies paid for a large proportion of the soldiers deployed by other coalition powers, peaking at about 450,000 in 1813.[4] The Royal Navy effectively disrupted France's extra-continental trade—both by seizing and threatening French shipping and by seizing French colonial possessions—but could do nothing about France's trade with the major continental economies and posed little threat to French territory in Europe. Also, France's population and agricultural capacity far outstripped that of Britain. However, Britain had the greatest industrial capacity in Europe, and its mastery of the seas allowed it to build up considerable economic strength through trade. That sufficed to ensure that France could never consolidate its control over Europe in peace. However, many in the French government believed that cutting Britain off from the Continent would end its economic influence over Europe and isolate it.

War of the Third Coalition 1805

As Britain was gathering the Third Coalition against France, Napoleon planned an invasion of Great Britain,[5][6][7][8] and massed 180,000 effectives at Boulogne. However, in order to mount his invasion, he needed to achieve naval superiority—or at least to pull the British fleet away from the English Channel. A complex plan to distract the British by threatening their possessions in the West Indies failed when a Franco-Spanish fleet under Admiral Villeneuve turned back after an indecisive action off Cape Finisterre on 22 July 1805. The Royal Navy blockaded Villeneuve in Cádiz until he left for Naples on 19 October; the British squadron subsequently caught and defeated his fleet in the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October (the British commander, Lord Nelson, died in the battle). Napoleon would never again have the opportunity to challenge the British at sea. By this time, however, Napoleon had already all but abandoned plans to invade England, and had again turned his attention to enemies on the Continent. The French army left Boulogne and moved towards Austria.

In April 1805, the United Kingdom and Russia signed a treaty with the aim of removing the French from the Batavian Republic (roughly present-day Netherlands) and the Swiss Confederation (Switzerland). Austria joined the alliance after the annexation of Genoa and the proclamation of Napoleon as King of Italy on 17 March 1805. Sweden, who had already agreed to lease Swedish Pomerania as a military base for British troops against France, formally entered the coalition on 9 August.

The Austrians began the war by invading Bavaria with an army of about 70,000 under Karl Mack von Leiberich, and the French army marched out from Boulogne in late July, 1805 to confront them. At Ulm (25 September–20 October) Napoleon surrounded Mack's army, forcing its surrender without significant losses. With the main Austrian army north of the Alps defeated (another army under Archduke Charles manoeuvred inconclusively against André Masséna's French army in Italy), Napoleon occupied Vienna. Far from his supply lines, he faced a larger Austro-Russian army under the command of Mikhail Kutuzov, with the Emperor Alexander I of Russia personally present. On 2 December, Napoleon crushed the joint Austro-Russian army in Moravia at Austerlitz (usually considered his greatest victory). He inflicted a total of 25,000 casualties on a numerically superior enemy army while sustaining fewer than 7,000 in his own force.

Austria signed the Treaty of Pressburg (26 December 1805) and left the Coalition. The Treaty required the Austrians to give up Venetia to the French-dominated Kingdom of Italy and the Tyrol to Bavaria.

With the withdrawal of Austria from the war, stalemate ensued. Napoleon's army had a record of continuous unbroken victories on land, but the full force of the Russian army had not yet come into play.

War of the Fourth Coalition 1806–1807

Within months of the collapse of the Third Coalition, the Fourth Coalition (1806–07) against France was formed by Prussia, Russia, Saxony, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In July 1806, Napoleon formed the Confederation of the Rhine out of the many tiny German states which constituted the Rhineland and most other western parts of Germany. He amalgamated many of the smaller states into larger electorates, duchies and kingdoms to make the governance of non-Prussian Germany smoother. Napoleon elevated the rulers of the two largest Confederation states, Saxony and Bavaria, to the status of kings.

In August 1806, the Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm III decided to go to war independently of any other great power except the distant Russia. The Russian army, an ally of Prussia, was still far away when Prussia declared war. In September, Napoleon unleashed all the French forces east of the Rhine. Napoleon himself defeated a Prussian army at Jena (14 October 1806), and Davout defeated another at Auerstädt on the same day. Some 160,000 French soldiers (increasing in number as the campaign went on) attacked Prussia, moving with such speed that they destroyed as an effective military force the entire Prussian army of 250,000—which sustained 25,000 casualties, lost a further 150,000 prisoners and 4,000 artillery pieces, and over 100,000 muskets stockpiled in Berlin. At Jena, Napoleon fought only a detachment of the Prussian force. Auerstädt involved a single French corps defeating the bulk of the Prussian army. Napoleon entered Berlin on 27 October 1806. He visited the tomb of Frederick the Great and instructed his marshals to remove their hats there, saying, "If he were alive we wouldn't be here today". In total Napoleon had taken only 19 days from beginning his attack on Prussia until knocking it out of the war with the capture of Berlin and the destruction of its principal armies at Jena and Auerstädt. By contrast, Prussia had fought for three years in the War of the First Coalition with little achievement.

In the next stage of the war the French drove Russian forces out of Poland and instituted a new state, the Duchy of Warsaw. Then Napoleon turned north to confront the remainder of the Russian army and to try to capture the temporary Prussian capital at Königsberg. A tactical draw at Eylau (7–8 February 1807) forced the Russians to withdraw further north. Napoleon then routed the Russian army at Friedland (14 June 1807). Following this defeat, Alexander had to make peace with Napoleon at Tilsit (7 July 1807). By September, Marshal Brune completed the occupation of Swedish Pomerania, allowing the Swedish army, however, to withdraw with all its munitions of war.

During 1807, Britain attacked Denmark and captured its fleet. The large Danish fleet could have greatly aided the French by replacing many of the ships France had lost at Trafalgar in 1805. The British attack helped bring Denmark into the war on the side of France.

At the Congress of Erfurt (September–October 1808), Napoleon and Alexander agreed that Russia should force Sweden to join the Continental System, which led to the Finnish War of 1808–09 and to the division of Sweden into two parts separated by the Gulf of Bothnia. The eastern part became the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland.

War of the Fifth Coalition 1809

-

Main article: War of the Fifth Coalition

The Fifth Coalition (1809) of the United Kingdom and Austria against France formed as the UK engaged in the Peninsular War against France.

Again the UK stood alone, and the sea became the major theatre of war against Napoleon's allies. During the time of the Fifth Coalition, the Royal Navy won a succession of victories in the French colonies.

On land, the Fifth Coalition attempted few extensive military endeavours. One, the Walcheren Expedition of 1809, involved a dual effort by the British Army and the Royal Navy to relieve Austrian forces under intense French pressure. It ended in disaster after the Army commander—John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham—failed to capture the objective, the naval base of French-controlled Antwerp. For the most part of the years of the Fifth Coalition, British military operations on land—apart from in the Iberian Peninsula—remained restricted to hit-and-run operations executed by the Royal Navy, which dominated the sea after having beaten down almost all substantial naval opposition from France and its allies and blockading what remained of France's naval forces in heavily fortified French-controlled ports. These rapid-attack operations functioned rather like exo-territorial guerrilla strikes: they aimed mostly at destroying blockaded French naval and mercantile shipping, and disrupting French supplies, communications, and military units stationed near the coasts. Often, when British allies attempted military actions within several dozen miles or so of the sea, the Royal Navy would arrive and would land troops and supplies and aid the Coalition's land forces in a concerted operation. Royal Navy ships even provided artillery support against French units when fighting strayed near enough to the coastline. However, the ability and quality of the land forces governed these operations. For example, when operating with inexperienced guerrilla forces in Spain, the Royal Navy sometimes failed to achieve its objectives simply because of the lack of manpower that the Navy's guerrilla allies had promised to supply.

Economic warfare also continued—the French Continental System against the British naval blockade of French-controlled territory. Due to military shortages and lack of organization in French territory, many breaches of the Continental System occurred as French-dominated states engaged in illicit (though often tolerated) trade with British smugglers. Both sides entered additional conflicts in attempts to enforce their blockade; the British fought the United States in the War of 1812 (1812–15), and the French engaged in the Peninsular War (1808–14). The Iberian conflict began when Portugal continued trade with the UK despite French restrictions. When Spain failed to maintain the continental system, the uneasy Spanish alliance with France ended in all but name. French troops gradually encroached on Spanish territory until they occupied Madrid, and installed a client monarchy. This provoked an explosion of popular rebellions across Spain. Heavy British involvement soon followed.

Austria, previously an ally of France, took the opportunity to attempt to restore its imperial territories in Germany as held prior to Austerlitz. Austria achieved a number of initial victories against the thinly spread army of Marshal Davout. Napoleon had left Davout with only 170,000 troops to defend France's entire eastern frontier (in the 1790s, 800,000 troops had carried out the same task, but holding a much shorter front).

Napoleon had enjoyed easy success in Spain, retaking Madrid, defeating the Spanish and consequently forcing a withdrawal of the heavily out-numbered British army from the Iberian Peninsula (Battle of Corunna, 16 January 1809). But when he left, the guerrilla war against his forces in the countryside continued to tie down great numbers of troops. Austria's attack prevented Napoleon from successfully wrapping up operations against British forces by necessitating his departure for Austria, and he never returned to the Peninsula theatre. In his absence and that of his best marshals (Davout remained in the east throughout the war) the French situation in Spain deteriorated, and then became dire when Sir Arthur Wellesley arrived to take charge of British-Portuguese forces.

The Austrians drove into the Duchy of Warsaw, but suffered defeat at the Battle of Raszyn on 19 April 1809. The Polish army captured West Galicia following its earlier success.

Napoleon assumed personal command in the east and bolstered the army there for his counter-attack on Austria. After a few small battles, the well-run campaign forced the Austrians to withdraw from Bavaria, and Napoleon advanced into Austria. His hurried attempt to cross the Danube resulted in the massive Battle of Aspern-Essling (22 May 1809)— Napoleon's first significant tactical defeat. But the Austrian commander, Archduke Karl, failed to follow up on his indecisive victory, allowing Napoleon to prepare and seize Vienna in early July. He defeated the Austrians at Wagram, on 5–6 July (During this battle, Napoleon stripped Marshal Bernadotte of his title and ridiculed him in front of other senior officers. Shortly thereafter, Bernadotte took up the offer from Sweden to fill the vacant position of Crown Prince there. Later he would actively participate in wars against his former Emperor).

The War of the Fifth Coalition ended with the Treaty of Schönbrunn (14 October 1809). In the east, only the Tyrolese rebels led by Andreas Hofer continued to fight the French-Bavarian army until finally defeated in November 1809, while in the west the Peninsular War continued.

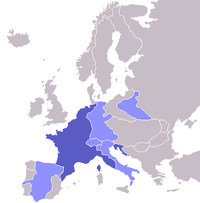

In 1810, the French Empire reached its greatest extent. On the continent, the British and Portuguese remained restricted to the area around Lisbon (behind their impregnable lines of Torres Vedras) and to besieged Cadiz. Napoleon married Marie-Louise, an Austrian Archduchess, with the aim of ensuring a more stable alliance with Austria and of providing the Emperor with an heir (something his first wife, Josephine, had failed to do). As well as the French Empire, Napoleon controlled the Swiss Confederation, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Italy. Territories allied with the French included:

- the Kingdom of Spain (under Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's elder brother)

- the Kingdom of Westphalia (Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon's younger brother)

- the Kingdom of Naples (under Joachim Murat, husband of Napoleon's sister Caroline)

- the Principality of Lucca and Piombino (under Elisa Bonaparte (Napoleon's sister) and her husband Felice Baciocchi);

and Napoleon's former enemies, Prussia and Austria.

The Invasion of Russia 1812

The Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 resulted in the Anglo-Russian War (1807–12). Emperor Alexander I declared war on the United Kingdom after the British attack on Denmark in September 1807. British men-of-war supported the Swedish fleet during the Finnish War and had victories over the Russians in the Gulf of Finland in July 1808 and August 1809. However, the success of the Russian army on the land forced Sweden to sign peace-treaties with Russia in 1809 and with France in 1810 and to join the Continental Blockade against Britain. But Franco-Russian relations became progressively worse after 1810, and the Russian war with the UK effectively ended. In April 1812, Britain, Russia and Sweden signed secret agreements directed against Napoleon.

In 1812, Napoleon invaded Russia. He aimed to compel Emperor Alexander I to remain in the Continental System and to remove the imminent threat of a Russian invasion of Poland. The French-led Grande Armée, consisting of 650,000 men (270,000 Frenchmen and many soldiers of allies or subject areas), crossed the Niemen River on 23 June 1812. Russia proclaimed a Patriotic War, while Napoleon proclaimed a Second Polish war. The Poles supplied almost 100,000 troops for the invasion-force, but against their expectations, Napoleon avoided any concessions to Poland, having in mind further negotiations with Russia. Russia maintained a scorched-earth policy of retreat, broken only by the Battle of Borodino on 7 September 1812. This required the Grande Armée to adjust its methods of operation, but it refused to do so.[9] This refusal led to most of the losses of the main column of the Grande Armée, which in one case amounted to 95,000 troops in a single week.[10] The bloody confrontation of Borodino ended in a tactical defeat for Russia, thus opening the road to Moscow for Napoleon.[11]

By 14 September 1812, the Grande Armée had captured Moscow. But by then, the Russians had largely abandoned the city, even releasing prisoners from the prisons to inconvenience the French. Alexander I refused to capitulate, and the governor, Count Fyodor Vasilievich Rostopchin, ordered the city burnt to the ground.[12] With no sign of clear victory in sight, Napoleon began the disastrous Great Retreat from Moscow. The remnants of the Grande Armée crossed the Berezina River in November, and only 27,000 fit soldiers remained. Napoleon then left his army and returned to Paris to prepare to defend Poland against the advancing Russians. With some 380,000 men dead and 100,000 captured,[13] the situation seemed less dire than at first. The Russians had lost around 210,000 men, leaving their army depleted. But with their shorter supply lines, they could replenish their armies faster than the French.

War of the Sixth Coalition 1812–1814

Seeing an opportunity in Napoleon's historic defeat, Prussia, Sweden, Austria, and a number of German states re-entered the war. Napoleon vowed that he would create a new army as large as the one he had sent into Russia, and quickly built up his forces in the east from 30,000 to 130,000 and eventually to 400,000. Napoleon inflicted 40,000 casualties on the Allies at Lützen (2 May 1813) and Bautzen (20–21 May 1813). Both battles involved total forces of over 250,000, making them some of the largest conflicts of the wars so far.

Meanwhile, in the Peninsular War, Arthur Wellesley renewed the Anglo-Portuguese advance into Spain just after New Year in 1812, besieging and capturing the fortified towns of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, and in the Battle of Salamanca (which was a damaging defeat to the French). As the French regrouped, the Anglo–Portuguese entered Madrid and advanced towards Burgos, before retreating all the way to Portugal when renewed French concentrations threatened to trap them. As a consequence of the Salamanca campaign, the French were forced to end their long siege of Cadiz and to permanently evacuate the provinces of Andalusia and Asturias.

In a strategic move, Wellesley planned to move his supply base from Lisbon to Santander. The Anglo–Portuguese forces swept northwards in late May and seized Burgos. On 21 June, at Vitoria, the combined Anglo-Portuguese and Spanish armies won against Joseph Bonaparte, finally breaking the French power in Spain. The French had to retreat out of the Iberian peninsula, over the Pyrenees.

The belligerents declared an armistice from 4 June 1813 (continuing until 13 August) during which time both sides attempted to recover from the loss of approximately a quarter of a million total troops in the preceding two months. During this time Coalition negotiations finally brought Austria out in open opposition to France. Two principal Austrian armies took the field, adding an additional 300,000 troops to the Coalition armies in Germany. In total the Allies now had around 800,000 front-line troops in the German theatre, with a strategic reserve of 350,000 formed to support the frontline operations.

Napoleon succeeded in bringing the total imperial forces in the region to around 650,000—although only 250,000 came under his direct command, with another 120,000 under Nicolas Charles Oudinot and 30,000 under Davout. The remainder of imperial forces came mostly from the Confederation of the Rhine, especially Saxony and Bavaria. In addition, to the south, Murat's Kingdom of Naples and Eugène de Beauharnais's Kingdom of Italy had a total of 100,000 armed men. In Spain, another 150,000 to 200,000 French troops steadily retreated before Anglo–Portuguese forces numbering around 100,000. Thus in total, around 900,000 French troops in all theatres faced around 1,800,000 Coalition troops (including the strategic reserve under formation in Germany). The gross figures may mislead slightly, as most of the German troops fighting on the side of the French fought at best unreliably and stood on the verge of defecting to the Allies. One can reasonably say that Napoleon could count on no more than 450,000 troops in Germany—which left him outnumbered about four to one.

Following the end of the armistice, Napoleon seemed to have regained the initiative at Dresden (August 1813), where he defeated a numerically superior Coalition army and inflicted enormous casualties, while the French army sustained relatively few. However, the failures of his marshals and a slow resumption of the offensive on his part cost him any advantage that this victory might have secured. At the Battle of Leipzig in Saxony (16–19 October 1813), also called the "Battle of the Nations", 191,000 French fought more than 300,000 Allies, and the defeated French had to retreat into France. Napoleon then fought a series of battles, including the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube, in France itself, but the overwhelming numbers of the Allies steadily forced him back. His remaining ally Denmark-Norway became isolated and fell to the coalition.

The Allies entered Paris on 30 March 1814. During this time Napoleon fought his Six Days Campaign, in which he won multiple battles against the enemy forces advancing towards Paris. However, during this entire campaign he never managed to field more than 70,000 troops against more than half a million Coalition troops. At the Treaty of Chaumont (9 March 1814), the Allies agreed to preserve the Coalition until Napoleon's total defeat.

Napoleon determined to fight on, even now, incapable of fathoming his massive fall from power. During the campaign he had issued a decree for 900,000 fresh conscripts, but only a fraction of these ever materialized, and Napoleon's increasingly unrealistic schemes for victory eventually gave way to the reality of the hopeless situation. Napoleon abdicated on 6 April. However, occasional military actions continued in Italy, Spain, and Holland throughout the spring of 1814.

The victors exiled Napoleon to the island of Elba, and restored the French Bourbon monarchy in the person of Louis XVIII. They signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau (11 April 1814) and initiated the Congress of Vienna to redraw the map of Europe.

Gunboat War 1807–1814

Initially, Denmark-Norway declared itself neutral in the Napoleonic Wars, established a navy, and traded with both sides. But the British attacked and captured or destroyed large portions of the Dano-Norwegian fleet in the First Battle of Copenhagen (2 April 1801), and again in the Second Battle of Copenhagen (August–September 1807). This ended the Dano-Norwegian neutrality, who engaged in a naval guerrilla war in which small gunboats would attack larger British ships in Danish and Norwegian waters. The Gunboat War effectively ended with a British victory at the Battle of Lyngør in 1812, involving the destruction of the last large Dano-Norwegian ship—the frigate Najaden.

War of 1812

-

Main article: War of 1812

Coinciding with the War of the Sixth Coalition but not considered part of the Napoleonic Wars by most Americans, the otherwise neutral United States, owing to various transgressions (such as impressment), by the British, declared war on the United Kingdom and attempted to invade Canada. The war ended in status quo ante bellum under the Treaty of Ghent, signed on 24 December 1814, though sporadic fighting continued for several months (most notably, The Surrender of Fort Bowyer). Apart from the seizing of then-Spanish Mobile by the United States, there was negligible involvement from other participants of the broader Napoleonic War. Notably, a series of British raids, later called the "Burning of Washington," would result in the burning of the White House, the Capitol, the Navy Yard, and other public buildings. The main effect of the War of 1812 on the wider Napoleonic Wars was to force Britain to divert troops, supplies and funds to defending Canada. This inadvertently helped Napoleon in that Britain could no longer use these troops, supplies and funds in the war against France.

War of the Seventh Coalition 1815

-

Main article: Seventh CoalitionSee also Hundred Days and the Neapolitan War between the Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire.

The Seventh Coalition (1815) pitted the United Kingdom, Russia, Prussia, Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands and a number of German states against France. The period known as the Hundred Days began after Napoleon left Elba and landed at Cannes (1 March 1815). Travelling to Paris, picking up support as he went, he eventually overthrew the restored Louis XVIII. The Allies rapidly gathered their armies to meet him again. Napoleon raised 280,000 men, whom he distributed among several armies. To add to the 90,000 troops in the standing army, he recalled well over a quarter of a million veterans from past campaigns and issued a decree for the eventual draft of around 2.5 million new men into the French army. This faced an initial Coalition force of about 700,000—although Coalition campaign-plans provided for one million front-line troops, supported by around 200,000 garrison, logistics and other auxiliary personnel. The Coalition intended this force to have overwhelming numbers against the numerically inferior imperial French army—which in fact never came close to reaching Napoleon's goal of more than 2.5 million under arms.

Napoleon took about 124,000 men of the Army of the North on a pre-emptive strike against the Allies in Belgium. He intended to attack the Coalition armies before they combined, in hope of driving the British into the sea and the Prussians out of the war. His march to the frontier achieved the surprise he had planned, catching the Anglo-Dutch Army in a dispersed arrangement. The Prussians had been more wary, concentrating 3/4 of their Army in and around Ligny. The Prussians forced the Armee du Nord to fight all the day of the 15th to reach Ligny in a delaying action by the Prussian 1st Corps.[14] He forced Prussia to fight at Ligny on 16 June 1815, and the defeated Prussians retreated in some disorder.[15] On the same day, the left wing of the Army of the North, under the command of Marshal Michel Ney, succeeded in stopping any of Wellington's forces going to aid Blücher's Prussians by fighting a blocking action at Quatre Bras. Ney failed to clear the cross-roads and Wellington reinforced the position. But with the Prussian retreat, Wellington too had to retreat. He fell back to a previously reconnoitred position on an escarpment at Mont St Jean, a few miles south of the village of Waterloo.

Napoleon took the reserve of the Army of the North, and reunited his forces with those of Ney to pursue Wellington's army, after he ordered Marshal Grouchy to take the right wing of the Army of the North and stop the Prussians re-grouping. In the first of a series of miscalculations, both Grouchy and Napoleon failed to realize that the Prussian forces were already reorganized and were assembling at the village of Wavre. In any event the French army did nothing to stop a rather leisurely retreat that took place throughout the night and into the early morning by the Prussians.[16] As the 4th, 1st, and 2nd Prussian Corps marched through the town towards the Battlefield of Waterloo the 3rd Prussian Corp took up blocking positions across the river, and although Grouchy engaged and defeated the Prussian rearguard under the command of Lt-Gen von Thielmann in the Battle of Wavre (18–19 June) it was 12 hours too late. In the end, 17,000 Prussians had kept 33,000 badly needed French reinforcements off the field.

Napoleon delayed the start of fighting at the Battle of Waterloo on the morning of 18 June for several hours while he waited for the ground to dry after the previous night's rain. By late afternoon, the French army had not succeeded in driving Wellington's forces from the escarpment on which they stood. When the Prussians arrived and attacked the French right flank in ever-increasing numbers, Napoleon's strategy of keeping the Coalition armies divided had failed and a combined Coalition general advance drove his army from the field in confusion.

Grouchy organized a successful and well-ordered retreat towards Paris, where Marshal Davout had 117,000 men ready to turn back the 116,000 men of Blücher and Wellington. Militarily, it appeared quite possible that the French could defeat Wellington and Blücher, but politics proved the source of the Emperor's downfall. In any event Davout was defeated at Issy and negotiations for surrender had begun.

On arriving at Paris three days after Waterloo, Napoleon still clung to the hope of a concerted national resistance; but the temper of the chambers, and of the public generally, did not favour his view. The politicians forced Napoleon to abdicate again on 22 June 1815. Despite the Emperor’s abdication, irregular warfare continued along the eastern borders and on the outskirts of Paris until the signing of a cease-fire on 4 July. On 15 July, Napoleon surrendered himself to the British squadron at Rochefort. The Allies exiled him to the remote South Atlantic island of Saint Helena, where he died on 5 May 1821.

Meanwhile in Italy, Joachim Murat, whom the Allies had allowed to remain King of Naples after Napoleon's initial defeat, once again allied with his brother-in-law, triggering the Neapolitan War (March to May, 1815). Hoping to find support among Italian nationalists fearing the increasing influence of the Habsburgs in Italy, Murat issued the Rimini Proclamation inciting them to war. But the proclamation failed and the Austrians soon crushed Murat at the Battle of Tolentino (2 May to 3 May 1815), forcing him to flee. The Bourbons returned to the throne of Naples on 20 May 1815. Murat tried to regain his throne, but after that failed, a firing squad executed him on 13 October 1815.

Political effects

The Napoleonic Wars brought great changes both to Europe and the Americas. Napoleon had succeeded in bringing most of Western Europe under one rule—a feat that had not been accomplished since the days of the Roman Empire (although Charlemagne had nearly done so around 800 CE). However, France's constant warfare with the combined forces of the other major powers of Europe for over two decades finally took its toll. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, France no longer held the role of the dominant power in Europe, as it had since the times of Louis XIV. In its place, the United Kingdom emerged as by far the most powerful country in the world and the Royal Navy gained unquestioned naval superiority across the globe. This, coupled with Britain's large and powerful industrial economy, made it perhaps the first truly global superpower and ushered in the Pax Britannia that lasted for the next 100 years.

In most European countries, the importation of the ideals of the French Revolution (democracy, due process in courts, abolition of privileges, etc.) left a mark. The increasing prosperity and clout of the middle classes became incorporated into custom and law, and the vast new wealth built on bourgeois activities, such as commerce and industry, meant that European monarchs found it difficult to restore pre-revolutionary absolutism, and had to keep some of the reforms enacted during Napoleon's rule. Institutional legacies remain to this day: many European countries have a civil-law legal system, with clearly redacted codes compiling their basic laws—an enduring legacy of the Napoleonic Code.

A relatively new and increasingly powerful movement became significant. Nationalism would shape the course of much of future European history; its growth spelled the beginning of some states and the end of others. The map of Europe changed dramatically in the hundred years following the Napoleonic Era, based not on fiefs and aristocracy, but on the basis of human culture, national origins, and national ideology. Bonaparte's reign over Europe sowed the seeds for the founding of the nation-states of Germany and Italy by starting the process of consolidating city-states, kingdoms and principalities.

The Napoleonic wars also played a key role in the independence of the American colonies from their European motherlands. The conflict significantly weakened the authority and military power of the Spanish Empire, especially after the Battle of Trafalgar, which seriously hampered the contact of Spain with its American possessions. Evidence of this are the many uprisings in Spanish America after the end of the war, which eventually lead to the wars of independence. In Portuguese America, Brazil experienced greater autonomy as it now served as seat of the Portuguese Empire and ascended politically to the status of Kingdom. These events also contributed to the Portuguese Liberal Revolution in 1820 and the Independence of Brazil in 1822.

After the war, in order to prevent another such war, Europe was divided into states according to the balance of power theory. This meant that, in theory, no European state would become strong enough to dominate Europe in the future.

Another concept emerged—that of a unified Europe. After his defeat, Napoleon deplored his unfinished dream to create a free and peaceful "European association" sharing the same principles, the same system of measurement, the same currency with different exchange rates and the same Civil Code. Although his defeat set back the idea by one-and-a-half centuries, it re-emerged after the end of the Second World War and is reminiscent of the European Union today.

Military legacy

The Napoleonic Wars also had a profound military impact. Until the time of Napoleon, European states employed relatively small armies, made up of both national soldiers and mercenaries. However, military innovators in the mid-18th century began to recognize the potential of an entire nation at war: a "nation in arms".[17]

France, with one of the largest populations in Europe by the end of the 18th century (27 million, as compared to the United Kingdom's 12 million and Russia's 35 to 40 million), seemed well poised to take advantage of the levée en masse. Because the French Revolution and Napoleon's reign witnessed the first application of the lessons of the 18th century's wars on trade and dynastic disputes, commentators often falsely assume that such ideas arose from the revolution rather than found their implementation in it.

But not all the credit for the innovations of this period go to Napoleon. Lazare Carnot played a large part in the reorganization of the French army from 1793 to 1794—a time which saw previous French misfortunes reversed, with Republican armies advancing on all fronts.

The sizes of the armies involved give an obvious indication of the changes in warfare. During Europe's major pre-revolutionary war, the Seven Years' War of 1756–1763, few armies ever numbered more than 200,000. By contrast, the French army peaked in size in the 1790s with 1.5 million Frenchmen enlisted. In total, about 2.8 million Frenchmen fought on land and about 150,000 at sea, bringing the total for France to almost 3 million combatants.

The UK had 747,670 men under arms between 1792 and 1815, and had about 250,000 personnel in the Royal Navy. [citation needed] In September 1812, Russia had about 904,000 enlisted men in its land forces, and between 1799 and 1815 a total of 2.1 million men served in the Russian army, with perhaps 400,000 serving from 1792 to 1799. A further 200,000 or so served in the Russian Navy from 1792 to 1815. [citation needed] There are no consistent statistics for other major combatants. Austria's forces peaked at about 576,000 and had little or no naval component. [citation needed] Apart from the UK, Austria proved the most persistent enemy of France, and one can reasonably assume that more than a million Austrians served in total. [citation needed] Prussia never had more than 320,000 men under arms at any time, only just ahead of the UK. [citation needed; this statement contradicts the first sentence in this paragraph.] Spain's armies also peaked at around 300,000 men, not including a considerable force of guerrillas. [citation needed] Otherwise only the United States (286,730 total combatants), the Maratha Confederation, the Ottoman Empire, Italy, Naples and the Duchy of Warsaw ever had more than 100,000 men under arms. Even small nations now had armies rivalling the size of the Great Powers' forces of past wars. However, one should bear in mind that the above numbers of soldiers come from military records and in practice the actual numbers of fighting men would fall below this level due to desertion, fraud by officers claiming non-existent soldiers' pay, death and, in some countries, deliberate exaggeration to ensure that forces met enlistment-targets. Despite this, the size of armed forces expanded at this time.

The initial stages of the Industrial Revolution had much to do with larger military forces—it became easy to mass-produce weapons and thus to equip significantly larger forces. The UK served as the largest single manufacturer of armaments in this period, supplying most of the weapons used by the Coalition powers throughout the conflicts (although using relatively few itself). France produced the second-largest total of armaments, equipping its own huge forces as well as those of the Confederation of the Rhine and other allies.

Napoleon himself showed innovative tendencies in his use of mobility to offset numerical disadvantages, as brilliantly demonstrated in the rout of the Austro-Russian forces in 1805 in the Battle of Austerlitz. The French Army reorganized the role of artillery, forming independent, mobile units, as opposed to the previous tradition of attaching artillery pieces in support of troops. Napoleon standardized cannonball sizes to ensure easier resupply and compatibility among his army's artillery pieces. [citation needed; Napoleon did not standardize the sizes; it was done by the manufacturer.]

Another advance affected warfare: the semaphore system had allowed the French War-Minister, Carnot, to communicate with French forces on the frontiers throughout the 1790s. The French continued to use this system throughout the Napoleonic wars. Additionally, aerial surveillance came into use for the first time when the French used a hot-air balloon to survey Coalition positions before the Battle of Fleurus, on 26 June 1794. Advances in ordnance and rocketry also occurred in the course of the conflict.

Last veterans

- Geert Adriaans Boomgaard (1788–1899) was the last surviving veteran. He fought for France in the 33ème Régiment Léger [18]

- Louis Victor Baillot (1793–1898) also from France, was the last Battle of Waterloo veteran. He also saw action at the siege of Hamburg.(See a 1898 photography)

- Pedro Martinez (1789–1898) was the last Battle of Trafalgar veteran. He served in the Spanish navy on San Juan Nepomuceno.[18]

- Josephine Mazurkewicz (1784–1896) was the last female veteran. She was an assistant surgeon in Napoleon's army and later participated in the Crimean War.

- Pvt Morris Shea (1795–1892) of the 73rd Foot was the last British veteran.[19]

- Sir Provo Wallis (1791–1892) was the last Royal Navy officer. He saw action on HMS Shannon during the War of 1812.

- Pictures of French veterans in uniform

In fiction

- Leo Tolstoy's epic novel, War and Peace recounts Napoleon's wars between 1805 and 1812 (especially the disastrous 1812 invasion of Russia and subsequent retreat) from a Russian perspective.

- Stendhal's novel The Charterhouse of Parma opens with a ground-level recounting of the Battle of Waterloo and the subsequent chaotic retreat of French forces.

- Les Misérables by Victor Hugo takes place against the backdrop of the Napoleonic War and subsequent decades, and in its unabridged form contains an epic telling of the Battle of Waterloo.

- Adieu is a novella by Honoré de Balzac in which can be found a short description of the French retreat from Russia, particularly the battle of Berezina, where the fictional couple of the story are tragically separated. Years later after imprisonment, the husband returns to find his wife still in a state of utter shock and amnesia. He has the battle and their separation reenacted, hoping the memory will heal her state.

- William Makepeace Thackeray's novel Vanity Fair takes place during the Napoleonic Wars—one of its protagonists dies at the Battle of Waterloo.

- The Duel, a short story by Joseph Conrad, recounts the story based on true events of two French Hussar officers who carry a long grudge and fight in duels each time they meet during the Napoleonic wars. The short story was adapted by director Ridley Scott into the 1977 Cannes Film Festival's Palme d'Or winning film The Duellists.

- The Temeraire series by Naomi Novik takes place in alternate-universe Napoleonic Wars where dragons exist and serve in combat.

- The Lord Ramage series by Dudley Pope takes place during the Napoleonic Wars.

- Charlotte Brontë's novel Shirley (1849), set during the Napoleonic Wars, explores some of the economic effects of war on rural Yorkshire.

- Le Colonel Chabert by Honoré de Balzac. After being severely wounded during the battle of Eylau (1807), Chabert, a famous colonel of the cuirassiers, was erroneously recorded as dead and buried unconscious with French casualties. After extricating himself from his own grave and is nursed back to health by local peasants, it takes several years for him to recover. When he returns in the Paris of the Bourbon Restoration, he discovers that his "widow", a former prostitute that Chabert made rich and honourable, has married the wealthy Count Ferraud. She has also liquidated all of Chabert's belongings and pretends to not recognize her first husband. Seeking to regain his name and monies that were wrongly given away as inheritance, he hires Derville, an attorney, to win back his money and his honor.

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, père starts during the tail-end of the Napoleonic Wars. The main character, Edmond Dantès, suffers imprisonment following false accusations of Bonapartist leanings.

- The novelist Jane Austen lived much of her life during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and two of her brothers served in the Royal Navy. Austen almost never refers to specific dates or historical events in her novels, but wartime England forms part of the general backdrop to several of them: in Pride and Prejudice (1813, but possibly written during the 1790s), the local militia (civilian volunteers) has been called up for home defence and its officers play an important role in the plot; in Mansfield Park (1814), Fanny Price's brother William is a midshipman (officer in training) in the Royal Navy; and in Persuasion (1818), Frederic Wentworth and several other characters are naval officers recently returned from service.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Brigadier Gerard serves as a French soldier during the Napoleonic Wars

- Jeanette Winterson's 1987 novel The Passion (book)

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's book The Idiot had a character, General Ivolgin, who witnessed and recounted his relationship with Napoleon during the Campaign of Russia.

- The Bloody Jack book series by Louis A. Meyer is set during the Second Coalition of the Napoleonic Wars, and retells many famous battles of the age. The heroine, Jacky, soon meets none other than Bonaparte himself.

- The Aubrey–Maturin series of novels is a sequence of 20 historical novels by Patrick O'Brian portraying the rise of Jack Aubrey from Lieutenant to Rear Admiral during the Napoleonic Wars.

- The Sharpe series by Bernard Cornwell star the character Richard Sharpe, a soldier in the British Army, who fights throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

- The Hornblower books by C.S. Forester follow the naval career of Horatio Hornblower during the Napoleonic Wars.

- The Napoleonic Wars provide the backdrop for The Emperor, The Victory, The Regency and The Campaigners, Volumes 11, 12, 13 and 14 respectively of The Morland Dynasty, a series of historical novels by author Cynthia Harrod-Eagles.

- The Richard Bolitho series by Alexander Kent novels portray this period of history from a naval perspective.

- Dinah Dean's series of historical novels are set against the background of the Napoleonic Wars and are told from a Russian perspective - "The Road to Kaluga", "Flight From the Eagle", "The Eagle's Fate", "The Wheel of Fortune", "The Green Gallant" - follow a small group of soldiers (and their relatives) over months of campaigning from the fall of Moscow up to the liberation of Paris, the last 3 books - "The Ice King", "Tatya's Story", "The River of Time" - fall some years later but have the same cast of characters.

- Bryan Talbot's graphic novel Grandville is set in an alternate history in which France won the Napoleonic War, invaded Britain and guillotined the British Royal Family.

- Julian Stockwin's Thomas Kydd series portrays one man's journey from pressed man to Admiral in the time of the French and Napoleonic Wars

- Simon Scarrow - Napoleonic series. Rise of Napoleon and Wellington from humble beginnings to history's most remarkable and notable leaders. 4 books in the series.

See also

- Grande Armée

- Coalition forces of the Napoleonic Wars

- British Army during the Napoleonic Wars

- Imperial and Royal Army during the Napoleonic Wars

- Royal Prussian Army of the Napoleonic Wars

- Imperial Russian Army

- Eastbourne Redoubt

- European Restoration (1815–1848)

- Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830)

- Hundred Years' War

- List of Napoleonic battles

- Martello tower

- Military career of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Military history of France

- Military history of the peoples of the British Isles

- World War I

- World War II

- Strategy of the central position

- British invasions of the Río de la Plata

- List of wars and disasters by death toll

Notes

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall (2004). Empire, The rise and demise of the British world order and the lessons for global power. Basic Books. ISBN 0465023282.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6247-2, 215.

- ↑ Buffinton, Arthur H. The Second Hundred Years' War, 1689–1815. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1929. See also: Crouzet, Francois. "The Second Hundred Years War: Some Reflections". French History 10 (1996), pp. 432–450. and Scott, H. M. Review: "The Second 'Hundred Years War' 1689–1815". The Historical Journal 35 (1992), pp. 443–469.

- ↑ Kennedy, Paul, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers - economic change and military conflict from 1500 to 2000 (London 1989), pp. 128-9

- ↑ "Napoleon I - MSN Encarta". Napoleon I - MSN Encarta. Encarta.msn.com. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761566988/napoleon_i.html. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ↑ The Geopolitics of Anglo-Irish Relations in the Twentieth Century P103

- ↑ National Maritime Museum

- ↑ Letter at the time

- ↑ Riehn, Richard K. pp. 138–140

- ↑ Reihn, Richard K, p.185

- ↑ Riehn, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ With Napoleon in Russia, The Memoirs of General Coulaincourt, Chapter VI 'The Fire' pp. 109–107 Pub. William Morrow and Co 1945

- ↑ The Wordsworth Pocket Encyclopedia, page 17, Hertfordshire 1993

- ↑ Hofschroer, pp. 171-191

- ↑ Hofschroer, pp. 255-257

- ↑ Hofschroer, pp 325-330

- ↑ "Napoleon's Total War". HistoryNet.com. http://www.historynet.com/wars_conflicts/napoleonic_wars/6361907.html. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Derniers vétérans de l'Armée napoléonienne, Premier Empire". Derniersveterans.free.fr. http://derniersveterans.free.fr/napoleon1.html. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ↑ "Photos of Napoleonic War Veterans in Wars in History Channel". Boards.historychannel.com. 31 May 2008. http://boards.historychannel.com/thread.jspa?threadID=520002112. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

References

- Asprey, Robert (2000). The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04879-X.

- Blanning, T. C. W. (2002). The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198227450.

- Cronin, Vincent (1994). Napoleon. HarperCollins. ISBN 0006375219.

- Pope, Stephen (1999). The Cassel Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Cassel. ISBN 0-304-35229-2.

- Schom, Alan (1998). Napoleon Bonaparte: A Life. Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092958-8.

- Tombs, Robert and Isabelle (2006). That Sweet Enemy. William Heinemann. ISBN 978-1-4000-4024-7.

- Zamoyski, Adam (2004). Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-718489-1.

External links

- The Napoleonic Wars Exhibition held by The European Library

- 15th Kings Light Dragoons (Hussars) Re-enactment Regiment

- 2nd Bt. 95th Rifles Reenactment and Living History Society

- The Napoleonic Wars Collection Website

- Napoleon, His Army and Enemies

- Napoleonic Guide

- Napoleonic Wars from the United States Military Academy

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||